Zane’s mother looked exhausted. I asked her if all was well.

“He won’t go to sleep unless I’m with him, he is taking forever to fall asleep and waking me up several times every night,” she sighed. “It is exhausting.”

“How come?” I asked, looking from the preschooler to his mother.

“It’s the monsters,” he chirped to clarify.

“For the hundredth time, Zane,” his mom exasperated, “there is no such things as monsters and there are certainly none in your room!”

“Is too!” his lower lip tightened in determination then began to tremble.

Zane’s mom took in a long breath and mouthed a silent “help.”

I smiled gently. The matter of monsters comes up often. Many young children–especially between four and six years of age–go through a period where they fear monsters. Under the bed, in the closet, behind the curtains/desk/wardrobe/chair, camouflaged among the stuffed animals on the top shelf … At the age where imagination and reality can merge and the veil between what’s real and what could be is thin, many children find the dark ominous and fear the parting with parents for the night and being left to their own thoughts and imagination. They are often too young to verbalize what it is they fear, exactly, but the feelings are still there: scary, dark, sneaky; the territory and making of monsters.

Scared or fearing to become so, they plead, coerce, and cry for their parents to stay and make sure they are okay.

Some are reassured by the adult checking under bed or dressers. For others, securing the closet door closed can suffice. However, for many, the fear remains in the ‘what if’ category: “what if the monster comes later?”, “what if the monster opens the door?”, “what if it is invisible and you can’t see it?”, “what if it just pretending to be my shoes but it will scare me later?”

Perception, reality, and belief make a sticky trio; and declaring monsters nonexistent rarely helps. To many children–as with Zane–this only makes the fear grow further and adds frustrated loneliness onto it, making nighttime doubly scary.

Zane’s mother needed her sleep. Zane needed his to feel safe. It was time to bring out the ‘big guns.’

I looked at the boy. A messy head of curls, brown piercing eyes under thick brows, a smattering of freckles on a button nose, wide lips, and a tongue that likes to slip out during speech and activity regardless of whether its presence is required (the tongue thrust being the main reason he sees me for speech-therapy).

The little boy regarded me. He needed to ascertain whose side I was on. “I have monsters,” he announced, “under my bed.”

“Yikes,” I replied. “This sounds scary.”

He smiled and turned to glare victoriously at his mommy.

She looked at me with uncertainty.

“You also see monsters!?” he checked, suddenly a bit wary of the possibility. Monsters being real is one thing. Monsters being REAL is quite another.

“Nah,” I shook my head. “But you say you do, so maybe they are there.”

He nodded quickly.

“What do they look like?” I wondered aloud.

“I don’t know!” he exclaimed. “They are hiding under my bed and it’s dark.” He followed that obvious fact with an ‘adults-can-be-so-thick’ look.

“Oh.” I demurred. “What if you turn on the light?”

“You can’t see them in the light. They do magic.”

“Hmm…”

“If I go to sleep by myself they will come and get me,” he warned. “Mommy says they not there but they are.”

“Well then,” I breathed. “I’m not in your house and I haven’t seen them, but just in case they are there, have you tried telling them you don’t want them there?”

“They don’t know English,” he responded.

“They don’t?” I let my voice rise some.

“No!” he explained, “they only speak Monster.”

“Hmm…”

He nodded sagely.

“…and they eat children,” he added for emphasis, then his eyes grew big with fright at the possibility of his own words and he backpedaled, “…um, maybe … if they really hungry.”

“We can’t let that happen,” I said.

He nodded again, reached for my hand.

I squeezed his little palm in reassurance. Children may be small but their fears can still be big, and their imaginations; bigger.

“Good thing we know what to do,” I stated.

He looked at me hopefully.

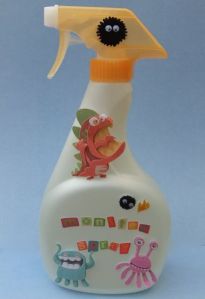

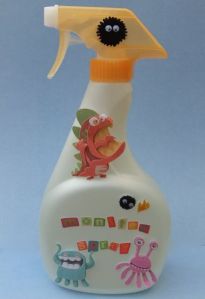

I pursed my lips in contemplation. “Have you tried Monster Spray?”

“Monster Spray?” This sounded intriguing.

“Yeah. They hate the stuff. Makes their noses itch.”

His eyes grew again, this time with wonder. He looked at his mom, clearly expecting her to know everything there is to know about sprays and all manner of remedies.

She raised her palms up in bewilderment and gave me an ‘I hope you know what you are doing’ glare.

“It works every time,” I reassured both of them.

“What’s Monster Spray?” Zane asked. “Mommy, you have to listen, too,” he ordered. “Because you didn’t learn it yet.”

I swallowed a chuckle. I was waiting to see how he would get back at her for not believing him that monsters waited under his bed waiting to eat children (maybe … if they really hungry…).

“It’s a spray and it makes monsters go away. It smells the same as an air freshener or perfume. The monsters don’t know the difference,” I said meaningfully. Mom’s eyebrows lifted and the corner of her month twitched a bit. Good. One aboard.

“Like in the bathroom?” Zane’s eyes narrowed suspiciously.

“Sort of. Doesn’t have to be the same one, though. You can pick any scent you like. They hate all of them. Makes their noses itch. Here is what you have to do. You listening?

He was.

“First, you find a spray that smells good to you. Mommy can help you choose. Next you make a sign that says “Monster Spray” and you tape it on the bottle …”

He nodded in approval. It was important to label things. Especially when it came to monsters.

“…and before you go to sleep you spray a bit under your bed, and if you want you can spray a little in the air, and that’s it. If the monsters are there they will say: ‘Oh, no, Monster Spray, we better come another day!’ and they’ll go away.”

Zane’s jaw hung open in delight. “For really?”

“Yep,” I nodded. “Works every time. If there are monsters there, they’ll run away from the monster spray.”

“What if they come tomorrow?”

“If they come another day, they’ll have to deal with more monster spray … and they’ll say: ‘Oh, no, Monster spray …”

“… better come another day!” he completed, his eyes shining.

“So we’ll have to do this forever?” Zane’s mom. I could sense her wariness about committing to nightly spray-bottle battles till Zane was in college.

“Oh, no,” I clarified. “You see, once you do it a few times, if the monsters come again they will say: ‘Oh no, more Monster Spray; we better go another way.’ They hate this stuff so much, they will tell all their monster friends to go another way!”

“Better go another way!” Zane clapped his hands, intoning, “Oh, no, Monster Spray; better go another way! Hey!” he paused, “Spray-way!” he lisped. “It rhyme!”

“It does indeed!”

“Spray, spray, go away,” Zane sang to himself and doodled as I explained the ‘anti-monster process’ to his mother.

Any scented spray would work. Body mist or freshener or even bottled water with some essential oils, vanilla extract, or lavender for scent. The scent will help Zane remember that the ‘Monster Spray’ is working, and can make associations to feeling safe and in control. I recommended keeping the spray bottle within reach, in case he woke at night and needed a ‘booster squeeze.’

As we returned to speech-sound practice, we spent part of the session making a label with the words “Monster Spray” on it, complete with a drawing of a dark-green/red/black blob (“that’s the monster, but you can’t see it because it is under”) and a figure in a cape holding a spray bottle like a sword (“that’s me, because I am super-Zane”).

The progress report the following week was that the monsters had such itchy noses the first time Zane used the newly minted spray on them, that they declared right away: “Oh, no, Monster Spray; Better go another way.” When a few monsters did not get the memo and tried their luck a few nights later, Zane spritzed them and they reportedly scuttled away to warn all others that: “Zane has Monster Spray, better go another way!”

You must be logged in to post a comment.