Upcoming Webinar!

Communication and Collaboration: Multidisciplinary treatment of traumatized/dissociative children

Friday, May 20, 2016

2:00 PM – 3:30 PM Eastern Time

Registration now open! (please see disclaimer in bottom of post)

Photo Credit: A.A.

Abstract

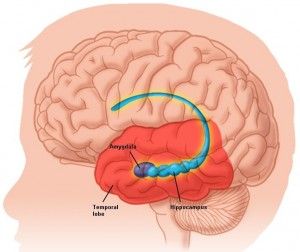

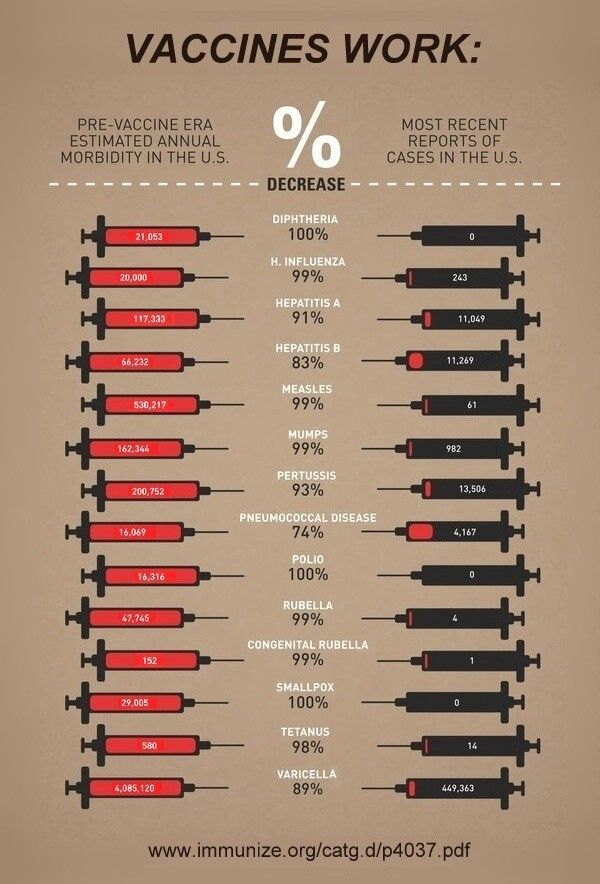

Treatment of traumatized and dissociative children is most often discussed in the context of psychotherapy. However, traumatized and/or dissociated children often come into contact with additional professionals. Like all youngsters, traumatized children need to manage everyday interactions with caregivers, educators, and routine childhood medical and dental care. Yet many also face clinical interactions with speech-language pathologists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, medical professionals, and more. This is because trauma places children at a high risk for developmental issues, and because children who already have developmental and/or health issues are highly vulnerable to trauma. In addition to clinical care, many traumatized children encounter legal personnel, forensic evaluators, child protective services, foster care staff, etc.

Posttraumatic and dissociative reactions are not limited to the therapist’s office. Just as communication issues aren’t segregated to speech-language pathologist’s office, asthma to the doctor’s, or sensory integration issues to occupational therapy. Various issues can complicate children’s presentation and behavior, and traumatized youngsters are often judged as difficult, aggressive, manipulative, immature, unpredictable, and inattentive. This can result in painful consequences (e.g. loss of placement, shaming, treatment failure), which further increase stress and reinforce the need for dissociative coping. In addition, caregivers routinely face challenges that can affect course of treatment, and professionals do not always ‘speak the same language’ when it comes to describing, assessing, and treating the child (and/or family). Even when professionals are trauma-aware, coordinated care is not always easy to achieve … and yet is essential for effective stabilization, minimizing compartmentalization, and carryover.

This webinar will look into the often complex realities of caring for traumatized/dissociative children and adolescents, the tapestries of clinical encounters many face, and how these may shift throughout infancy, childhood, and teen years. The challenges (and potential) of coordinated care and communication will be discussed, as would logistical and ethical limitations and suggestions for managing them. Clinical vignettes will serve as a window into ways for improving communication among child/family professionals, and will provide examples for practical solutions for increasing regulation and decreasing posttraumatic activation in all involved. The role of caregivers and the child as part of the team will also be examined.

Objectives

Upon completion of this webinar, participants will be able to:

- Identify the connection between trauma and care utilization in children and adolescents.

- Describe three challenges to coordinated care

- List five strategies therapists can apply to improve communication and coordination in the multi-disciplinary treatment of traumatized/dissociative children

For more information and to register

Disclaimer: I volunteer my time and expertise for this webinar, and do not receive any financial gain from it. Registration fees are collected by ISSTD, which hosts the webinar, is responsible for all fees and/or refunds, and provides an option for CEs for attendance.

You must be logged in to post a comment.