Things Kids Say

Connections

The boy, five years old, had his hands deep in soft dough. “What do butterflies eat?” There was a butterfly cutter among the shapes on the table, likely the inspiration.

“Nectar.”

“From the flowers?”

“Yep!”

Silence, a bit more kneading, pulling, twisting and squeezing. This kid has such high sensitivity to textures that it took three months of work with an excellent occupational therapist before he was willing to touch the dough, let alone let it squirt between his fingers. My work with him was reinforcing the OT work in the speech-and-language contexts. Children learn much better when their body is engaged.

“What do frogs eat?” He fingered the frog cutter, put it next to the butterfly one, compared their sizes, lightly pressed the edge of the frog shape into his ball of dough.

“Frogs eat mosquitos as well as other kinds of insects: flies and gnats and such.”

“Good.”

“How come?” I smiled.

“Because mosquitos eat people alive.” His big eyes hang on me, suddenly a little scared by his own repetition of words he’d heard, “but do they really eat people?”

“Not exactly, no. The female mosquito drinks blood for her food, but only a very little bit. It is very small and it doesn’t actually eat you.”

“Oh. Yucky.”

“Yeah, I would not want to be a mosquito.”

“Me neither!” Pause. “Frogs don’t mind, right?”

“Yep.” I can see another question coming.

“Who eats frogs?”

“Snakes do. Some other animals eat frogs, too, even some people eat frogs.”

“People!?” The munchkin was simultaneously impressed and repelled. “People don’t eat frogs, do they?” he turned to his mommy. Usually, I’m an acceptable source for information, but some things require a higher authority.

The mother nodded, amused. “In France they do. Maybe in some other countries.”

“Yuck.” he relished the word. “Yucky, yucky.” He twisted his lips in contemplation, and you could see the wheels turning in the little brain behind the hazel eyes and summer freckles. “But … frogs eat the mosquitos and the mosquito eat blood from people …” he let the question dangle.

I raised my eyebrows, waited.

“It’s like a circle.” He breathed. “It is everything connected!”

From the mouths of babes.

Half-Angel

What do you do with a grieving child?

You listen. You hold. You listen some more.

You offer tissues, you offer a hug. You answer lots of questions.

You nod. You tell stories. You honor the small memories told.

You come up with suggestions–or rather, embellish on those that the little one has.

You produce boxes (“too little”, “too big”, “too not-good”, “I don’t like it”, “okay, this one …”), find padding and ribbons and stickers, along with a few extra hugs.

You write what’s requested. Erase the letter that did not look perfect. Write it again. Erase. Write once more. You understand that it has to be just-so.

You provide blank paper and crayons, markers, highlighters, scissors. Play dough.

You oblige to search Google for questions your answers were not good enough, and come across five hundred other interesting things that lead to more questions. Distraction is good medicine, too.

You write down a protocol for ceremony, number the steps, change the order.

You make a headstone from tongue depressors and card stock. Give another hug.

You write the name of the departed. Erase it because it did not come out perfectly. Write. Erase. Write once more.

You draw a picture and told it “doesn’t even look like him.”

You are saved by a photo from the bowels of phone memory–a snapshot of happier times.

You give more hugs. Another tissue.

You stay with. You listen. You know that no small loss is small. That no one is truly replaceable, that loss is confusing and brings along with it the worry of losses far bigger and questions too scary for words. You don’t go where the child does not take you. You comfort, you understand.

What do you do with a grieving child?

You listen. You hug.

You promise not to forget.

You tuck the drawing in the folder (“but be careful”) to keep it safe.

And you use a tissue yourself, when the child wonders aloud if dead fish get to have wings and continues to answer himself: “Yeah, because they have fins, so Benny was already half-angel.”

Because I understand me!

She heard noises coming from her daughter’s room. A heated conversation, animated chattering.

She listened at the door. Changed tone, one voice, empathetic discussion. She peeked–no toys involved, no dolls. Just her four year old sitting on the bed, talking earnestly.

“Who are you talking to?” she asked.

“Me.”

“How come you’re talking to yourself?”

A surprised look, a ‘duh’ voice: “But Mommy! Because I understand me!”

What do you do with a melted child?

I could hear them before they even entered the building … his screech, her frustrated murmuring, unclear words with clear intent to hush and stop the fussing.

It did not get better in the vestibule, or the stairway. Screaming, banging on the rails (there’s fantastic echo in the building–apparently it is spectacularly irresistible for maximizing the effect of tantrums).

The mother’s pleas inched up in volume, from “stop this” to “please behave” and “you are making too much noise” to “other people are going to get mad at you” and “if you don’t stop this there’d be no playdates.” The immediate effect was a proportionate rise in the child’s loudness.

I decided to go meet them half-way. It is not something I usually do, so my very appearance in the hallway was enough to generate sufficient surprise to elicit momentary silence. I capitalized. “Sounds like you are having a hard day,” I noted, directing my words to both red-faced figures, one with mortification, one with the exertion of maximizing vocal output on steep stairs.

“I’m melting,” he noted, quite matter of fact, I might add.

“Oh,” I responded.

The mom looked from him to me and back again. “Melting?”

“A meltdown, I suppose,” I smiled, turned to the boy. “It sure sounds like a major meltdown.”

He nodded emphatically, satisfied.

“Do you think you had enough of a meltdown for one time?” I offered my hand to him. “It sounds pretty exhausting.”

He considered, placed his little hand in mine. Turned to his mother with a rather smug expression. “I done melting now.”

“I’m glad,” she managed.

“What was this about?” I wondered aloud.

“He wanted to be the one to press the button for the bus stop …”

“Ah.”

“But someone else on the bus already pressed it … so he refused to get off …”

I looked at him with a raised eyebrow. He nodded, approving of the testimony. “It was my turn to push the button,” he accused.

“Hmm, maybe other people on the bus didn’t know that.”

He looked shocked at the very notion. How could anyone not know what he clearly had?

We climbed. He pondered.

“It only got worse from there,” his mother added, still debriefing. “I had to carry him off the bus, screaming. He threw himself on the ground …”

It explained the stage of his clothing … it had rained earlier …

“He got himself all wet …” she sighed, “I’m sorry for bringing him in such a mess.”

He turned to her, his face a mask of indignation. “Of course I wet, Mama! I was melting!”

Happiness glide

“I had the best weekend ever!” the preschooler’s eyes sparkled.

“Oh, wow, that’s so great!” I responded, grinning. It is contagious, you know, this kind of zest for life. And the enthusiasm of this little one was particularly catching. He literally beamed delight.

“We had the best ever dinner and the best ever pizza!” he bounced on his heels, the words not coming nearly fast enough. “And I saw the best movie ever on the Netflix. And my grandpa makes the best popcorn and it like magic in the microwave and I have the best pajamas ever!”

“You have new pajamas?!” My monkey brain had to assume.

He paused and regarded me with some confusion. “I already HAVE the best pajamas ever! It’s superman pajamas!”

Silly me.

He kicked off his shoes and glided on the wood floor with his socks, balancing with his arms. “Wheee! Best floor ever!”

“Did you have the best weekend ever, too?” he added, not quite waiting for a response before sighing contentedly. “You did, right? Because it was the best weekend ever!”

The details change a bit; there’s not always popcorn, sometimes its just TV and not Netflix, sometimes it is the park, or playing ball, or baking cookies, or his dad reading him story. Doesn’t matter. The weekend is always–always–the best one ever.

And it makes for Happy Mondays; every one.

Truth Be Told–From the Mouths of Babes

“What does it mean, to tell the truth?”

A child asked me that. As usual, they are my greatest teachers. “What do you think?” I returned the question, wondering at the child’s working hypothesis (and chickening out just a little bit–let the munchkin do the hard work …).

I got the look I deserved, and: “To not be a liar.”

“Hmm,” I non-committed. “What does it mean to lie?”

“To say you didn’t do it but you did?” he tried. “And to be mean.”

I raised an eyebrow. This kid was good at reading body language.

“Yeah, because someone else get in trouble.”

“Oh, I can see how that would not be very nice, to get someone else in trouble. Anything else lying means?”

A moment of scrunched forehead. “Is it still lying even if you pretend you didn’t do it but you don’t say?”

“What do you think?”

A sage nod. A sigh. “Yeah, it still mean. Someone still get in trouble, right? Because the teacher think its them.”

“So…” I prompted (he was doing so well on his own, I felt like my words would be interfering).

“So … telling the truth is being not mean?” he ventured. His little face was quite serious, thinking this through.

“Hmm.”

“But truth is hard,” he sighed, a six-year-old summing up centuries of philosophy. “It can get you in trouble. … you know, if you did bad things.”

He paused. “But … then you can say sorry, maybe. Maybe you won’t be in trouble. … if you’re lucky.”

“Yeah, being honest can help.”

Big brown eyes hung onto mine. “What do you think is worser, being mean or being in trouble?”

Tough one. I’m returning it to him. “What do you think?”

“Being mean.” He did not hesitate. “Being mean is worser.”

“How come?” I pushed. Curious. Enchanted by this child.

“Oh … because … being mean makes me more in trouble,” he stated. Pointed to his midriff. “With my heart.”

Old soul, big spirit, that.

Proof of Trying

She came to session in a huff.

“I am SO bad at history,” she stated bitterly. “I hate history.”

After letting in a bit of sympathy and a bit of gentle urging, she pulled out a stapled test striped broad with red–remarks, circled words and crossed out answers–the teacher’s mutilation. A large C dominated the top of the page. She threw the paper on the table, her face a salad of emotions: regret, embarrassment, disgust, disappointment, sadness, frustration, despair, shame.

“I’m not taking this home,” she said. “Can you keep it in my file here instead?”

“How about we look at the test together,” I offered, skirting the question.

She frowned (kids always pick on adult evasive maneuvers …) but nodded grudgingly. We went over the questions and her answers. She was actually almost correct on most, just not quite as the teacher wanted. The girl misinterpreted directions on a couple but wrote accurate facts; misplaced a number on a date; confused an ambiguous passive tense and so got the answer wrong (trick question, that one was); wrote the wrong sequence of correctly memorized events …

The teacher gave no quarter for mistakes of any kind, no leeway. The red marks slashed through the test in an assured hand of criticism. To add insult to injury, the bottom of the second page read “Try harder next time” … harshly assuming that the effort was what lacked, rather than skill or speed of processing.

In effect, the mistakes were very good proof of trying. They were signposts of the effort put in by a child who finds memorizing difficult and worked hard to understand the unfurling of what happened to whom where and when and why. She knew the material, even if the test plumbed all her weak spots and completely ignored the many things she studied.

Comforted some by the validation of her work, she calmed, vindicated that she wasn’t “bad at history” and bolstered by understanding that while the teacher had the right to take off points for errors, there were many places where knowledge came through, if imperfectly.

For the rest of the session we worked on attending to test questions: identifying exactly what was asked, highlighting important words in questions and directions, re-wording it if necessary, reading all the answers before settling on the best one, writing down key-words. Strategies for testing.

In the end she left with the offending graded test in her backpack, ready to take it home and armed with the understanding of what she did right, not only what came out wrong. Still disappointed, she was at least no longer ashamed.

“I think Ms. J sure does loves red,” she noted, a bit of snark in her voice but humor finally restored. “Maybe someone should get her a green marker …”

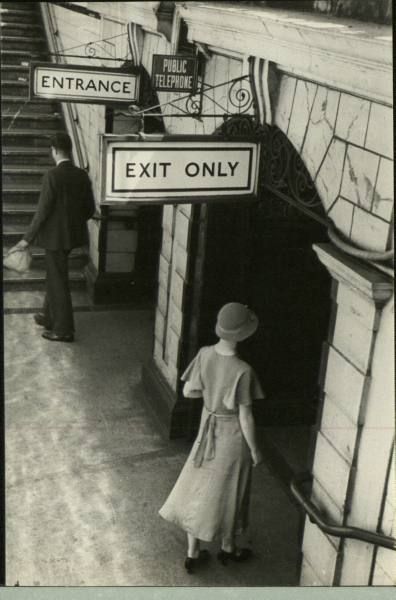

Rules? What Rules?

A friend sent me this photo, taken 1910 … and I thought, it was the best BEST example ever, of bending the rules … (or at least those rules that make no sense beyond to those who made them … )

I was reminded of it today, after speaking with a young boy who complained that he got into trouble–yet again–for breaking “another of the teacher’s stupid rules.”

The boy’s mother had her mouth already open to reprimand him for using a word one ‘should not say’ in the context of one’s educators … but I gave her one of my ‘please don’t’ looks … and she took a deep breath and nodded.

“What kind of rules?” I asked.

“Stupid ones,” he grumbled. Then seeing that I was actually waiting to hear an example, he sighed. “Like not being allowed to hold our pencils while we’re reading. She keeps taking points off when I break the rule.”

“Did she tell you why she doesn’t want you to do that?”

“I don’t know,” he shrugged, “because she said so?”

I chuckled. “Fair enough … sometimes grownups say that you should not do things just because they say so … but I was wondering if she ever actually told you why. Sounds to me she maybe has a reason–maybe kids play with their pencils? Drop them a lot and it is distracting? Doodle in the books?”

The boy peered at me with a look that let me know that I have just lost about 200 points of coolness in his view along with several dozen in the IQ department. “Sometimes we’re supposed to write in our books,” he stated, “… anyway, if she said it was for that it would make sense, sort of” he added. “I don’t drop mine. I just hold it. She doesn’t want us to hold the pencils just because.”

I raised an eyebrow. “Just because?”

“Yeah,” he stressed. “She said that we don’t need a pencil in our hands for our brain to read…” the boy pouted. “How does she know what my brain needs for reading? What if the pencil reminds my brain what the letters are?”

Point made.

I actually could see how it could do that.

I told the little guy that if it helps him to hold the pencil when he’s reading, to go ahead and do so.

He looked at me, suspicious. “It’ll get me in trouble.”

“Not if you tell her that I told you it’s okay for you to keep holding it if it helps your brain.” I smiled, more than a tad conspiring.

His eyes grew large, and the grin that followed had enough wattage to light up Manhattan’s night sky.

A Small Bewitching

She came up the stairs dragging a very sorry looking mop.

To my raised eyebrow, she smiled, “it’s a secret,” and said no more. She placed the mop in a corner (head double tied in a plastic bag per my insistence), and sat down to work. Once in a while she lifted her face to look at the mop’s handle with a little “I know something that you don’t but this is working really well so far” grin.

I was of course dying of curiosity but had to admire her resoluteness to not spill the beans. This was no easy feat for a girl who would usually share just about any tiny detail she could think of.

Not this time.

This cat, I could see, was not being let out of the bag. How apt, when we have been working on symbolic language, and how she adored the image of that specific idiom. Thought it was the funniest thing after being “all ears.”

When the mother came to pick her up at end of session, a storm paced near.

“What’s this?” The parent curled a lip.

“From outside,” the child replied regally and more than a little challenging.

The mother shook her head at the mop. (My thoughts exactly … from OUTSIDE? Who knew what peed on this, or worse, and why someone decided to toss out the scraggly mess! She brought this in here from OUTSIDE?!)

The child remain stoic. “I told you I’d figure it out,” she said cryptically.

“But …”

“And you said that if I found a way then I could AND that this can be a secret until Halloween! So you can’t say anything or you’ll tell!” the girl jumped in rapidly before the mother said something that would reveal what was to be kept hidden (and … I think, to prevent any conversation from putting her at a disadvantage …).

The mother looked at me helplessly but all that I could do was shrug slightly and observe. This was better than TV, definitely. I did not have a clue what was going on, but the child’s delight was fun to see. I did have to hand it to the gal: she clearly made a point and seemed to be driving it home (hopefully not literally … I could not see any cab driver happy to see this in the taxi … and was already thinking how there’d be some disinfecting on my end once this thing left my floor, plastic bag or not …).

A long moment ticked. Another.

“Okay!” the mother sighed. The girl’s grin was humongous.

“Okay?!” I could not help it. The girl picked this up from the garbage and it was okay?? This was not a woman who collected toss-out stuff from pavements, and I could not see her letting this into her house. I could barely believe I let it into mine …

“Oh, she means she’ll get me one!” the girl explained. Victorious. “She didn’t want to but I told her that I will find one myself … though,” she turned to her mother, all nectar and loving sweetness, “it WILL be so much nicer to have a new clean one to use …”

The girl grinned at my bewilderment and left hopping down the stairs. Her mother–I am not sure quite as relieved–carried the offensive mop between two careful fingers (“So it does not smear who knows on each of your steps,” the parent shuddered, keeping the bagged mop head well above the ground.)

Neither mother nor child offered explanation for the girl’s newly found interest in housekeeping. It remained a mystery to me.

Until today.

(Picture of an unrelated child in a similar costume …)

You must be logged in to post a comment.